ISSEP Honors the Legacy of Ernest Becker

By Kenneth Vail, Cleveland State University, & Sheldon Solomon, Skidmore College. November 29, 2023.

Ernest Becker and his Pulitzer Prize winning The Denial of Death (1973)

ISSEP is proud to celebrate and honor the legacy of Ernest Becker. Although his academic career was tragically cut short, his passion as an educator and the breadth of his thought were without limits. He embodied the indominable values of education and compassion—the goal to learn as much about ourselves and our world as possible, and to use that information to make the world a better place for others. In just 14 years, he authored 9 books, held 6 different professional appointments, defended academic freedoms, advocated for peace and social justice, and made important contributions that ultimately helped lead to the development of the science of existential psychology.

Here, we trace the contours of his educational and professional biography, from New York to California to Canada, followed by an appreciation of his three most mature works and the content of his contributions to existential psychological thought. We also reflect on the founding, mission, and contributions of the Ernest Becker Foundation, and then consider the influence of both Becker and the EBF on the science of existential psychology. Lastly, we are proud to describe how, with generous support from the EBF, the ISSEP is able to continue to honor the legacy of Ernest Becker through the continued operation of the EBF website (ernestbecker.org), the establishment of an annual set of Ernest Becker Honors (research grant, annual award, conference awards), and the continued cultivation and production of original Becker-related content on our own website (issep.org) each year.

ISSEP is proud to honor the legacy of Ernest Becker and the EBF in each of these various ways, and is looking forward to supporting the exploration and communication of scholarly engagement with Becker’s ideas through the science of existential psychology for decades to come!

Ernest Becker: Professional biography

Ernest Becker was born in September 1924 to Jewish immigrants in Springfield, Massachusetts. When WWII broke out, he served as infantry in the US Army and helped to liberate a Nazi concentration camp. Following the war, he completed his undergraduate degree at Syracuse University in upstate New York and then took a position as an administrative officer of the U.S. Embassy in Paris.

Eventually, however, he lost interest in the diplomatic corps, and in his 30s returned to Syracuse University for a graduate program in cultural anthropology. There, he studied under Douglas Haring, a specialist in Japanese philosophical anthropology, and completed his PhD in 1960 at the age of 36. Becker published the first of his nine books, Zen: A Rational Critique (1961), based on his dissertation’s critical analysis of the concepts of human life, individuation, and autonomy in Japanese Zen as compared to Chinese thought and Western psychotherapy.

Becker then took a position in the Department of Psychiatry at the Upstate Medical Center, also in Syracuse NY. While there, he developed a close friendship with Thomas Szasz—a tenured professor who had been rather loudly criticizing both the “medical model” and the role of authority (e.g., involuntary commitment) in psychiatric practices. Becker took part in Szasz’s discussion groups, participated in lecture symposia, and published various articles in psychiatric journals. Becker’s second book, The Birth and Death of Meaning (1962), and especially his third book The Revolution in Psychiatry (1964), were influenced by his time with Szasz and his circle.

However, by November 1962, the New York State Department of Mental Hygiene had lost their patience with Szasz’s attacks on their practices. So, they disciplined Szasz and effectively stripped him of his teaching privileges. Becker and several other young professors, who had not yet secured tenure, criticized the university and defended Szasz on the principle of academic freedom. In response, Becker and his colleagues were summarily fired.

He then spent a year writing and reflecting, mostly in Rome, Italy, before returning, at the age of 40, to the Syracuse University Department of Education and Sociology for the 1964-65 academic year. Although not particularly fond of students’ recreational activities of the 1960s, he did join their emerging political movements—openly supporting the civil rights movement, protesting the Vietnam war, and criticizing controlling educational practices. However, when he criticized the university for seeking and relying on funding from military and business interests, Syracuse fired him again.

Becker was able to secure a position at the University of California, Berkeley, in the Sociology Department for the 1965-66 year and in the Anthropology Department for the 1966-67 year. Here, he published his fourth book, Beyond Alienation (1967). His courses were broadly interdisciplinary, he readily applied concepts to current events, and his teaching style was theatrical—sometimes even involving costumes, props, and stage lighting. The students loved him and turned out for his courses in droves. The faculty and admin, however, were less than pleased and did not renew his contract. The students protested and rallied, thousands signed a petition to keep him, and the student government even voted to use student funds to pay his salary as a “Visiting Scholar.” But it was to no avail, as Berkeley showed Becker the door yet again.

In 1967, he managed to acquire a position teaching Social Psychology at San Francisco State University, and while there published his fifth and sixth books, The Structure of Evil (1968) and Angel in Armor (1969). However, SFU was a progressive place during a turbulent time. SFU students had formed the nation’s first Black Students Union and had been agitating for more inclusion of people of color both as greater portions of the student body and as official subjects of study (e.g., Ethnic Studies). When members of the Black Panthers were suspended, the student body went on strike from November 1968 to March 1969. The SFU President adopted a strong-arm approach, sending in police who engaged in violent clashes with students (Bates & Meraji, 2019). In support of the students, Becker and several other faculty colleagues resigned in protest.

His next, and final, position was at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, where he taught from 1969-74 in an interdisciplinary Department of Political Science, Sociology, and Anthropology (Martin, 2014). Here, he published his seventh book, The Lost Science of Man (1971), and a revised second edition of The Birth and Death of Meaning (1971). He also published his eighth book, The Denial of Death (1973), and had begun working on a sequel. However, he had been diagnosed with colon cancer in November 1972, and died just a year and half later, on March 6, 1974, in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada, at the relatively young age of 49. Two months after his death, his The Denial of Death won the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction, and the unfinished sequel was posthumously published as his ninth and final book, Escape From Evil (1975).

Becker’s contributions to existential psychological thought

Clockwise from top left: Ernest Becker; The Birth and Death of Meaning (1971); The Denial of Death (1973); and Escape from Evil (1974).

Becker’s work contributes to a rich tradition of existentialist thinking which argues that the human phenomenological experience is profoundly shaped by the challenge of authentic living in a world where we know that we die, and where meaning and purpose are often little more than arbitrary human constructions. In that regard, his work extends the philosophies of giants like Soren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and builds upon the work of psychologists such as Norman O. Brown, Erich Fromm, and especially Freud’s rebellious protégé—Otto Rank. Of Becker’s nine books, three stand out as his most mature contributions to the existentialist tradition: The Birth and Death of Meaning, 2nd ed. (1971), The Denial of Death (1973), and Escape From Evil (1975).

The Birth and Death of Meaning, 2nd ed. (1971) explores humankind’s gradual transformation from the simple-minded ape, concerned primarily with immediate biological needs, into a more complex animal capable of symbolic thinking and linguistic communication of meaning, self-awareness and self-reflective thought, and freedom to choose and pursue one’s own self-determined course of actions. Becker also highlighted the contradiction between the human’s body and mind—that we humans are creatures of the natural world, like any other animal, and yet our abstract symbols and meanings create the opportunity for a supernatural experience. In the revised edition, incorporating his matured appreciation of the human fear of death, he argued that whereas our creaturely bodies are born and die, our meanings can transcend those physical boundaries and can define a self and a society in symbolic terms that defy death.

The Denial of Death (1973) built upon those foundations, arguing that human cultural ideas and activities are, essentially, elaborate symbolic defenses against the concept of mortality. Whereas the physical body obviously lives and dies, just like any other animal, the symbolic self can transcend those boundaries. Thus, Becker argued that, to protect themselves against their primordial fear of death, people cultivate abstract societal meaning systems (cultural worldviews) that transcend physical death and strive to become “heroes” of those systems. In that way, we would, in a sense, earn our place among the stars, becoming a part of something much larger and longer lasting than our physical bodies. To the extent that we learn and internalize those immortality projects—whether religious or, increasingly, secular—we can feel meaning and purpose in our lives.

In The Denial of Death, but especially in Escape From Evil (1975), Becker explored the idea that “evil,” whether it be monumental or mundane, often stems from the clash of cultures in this existential context. The emergence of alternative, competing cultural worldviews threaten the psychological utility of one’s own as a meaningful path to a death denying sense of permanence—and therefore the alternatives must either be assimilated, accommodated, or annihilated. Becker’s hope was that an improved understanding of these processes would enable humankind to be able to better control them, so that people might live together more peacefully.

The Ernest Becker Foundation: Founding, Mission, & Contributions

Neil J. Elgee, M.D., (1926-2020), Founder and President of the EBF.

Born in 1926, Neil J. Elgee spent his life influenced by the intersection of death, violence, and ideas. After enduring WWII in his teens, he went on to medical school, residency, and research fellowship training, as well as military service, before a career practicing Internal Medicine from 1957-1993. During the height of the Cold War, in 1977, one of Neil’s patients convinced him to read Ernest Becker’s Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death. The book dramatically challenged the way he viewed the world, so much so that it caused him to change his medical practice, his thinking and beliefs, and indeed his entire understanding of the fundamental “realities” of the human condition.

Struck by the feeling that Becker’s insights were profoundly important, and written with brilliant clarity and accessibility, Neil began discussing and recommending Becker’s work with everyone he encountered. He discussed Becker’s ideas with patients, medical residents, and colleagues, and he wrote about Becker’s ideas in the medical literature (e.g., Elgee, 2005). To his disappointment in those early years, his enthusiasm for Becker’s insight was often met with a merely lukewarm reception. However, by the time Neil retired from medicine in 1993, some 15 years after his first encounter with Becker’s work, the situation had changed and people had become much more receptive to Becker’s ideas.

Thus, on Halloween of 1993, Neil Elgee and eight others formed the Ernest Becker Foundation. The EBFs guiding mission was: “To advance the understanding of the role of death denial in everyday life, so that we may live together more peacefully.” Indeed, over the course of 30 years (1993-2023), the EBF brought together people from all walks of life to further explore the role of death denial in everyday living. The EBF supported the development of terror management theory and its research in the science of existential psychology; and it sponsored countless salons, conferences, and webinars, featuring Becker-related work across the sciences, arts, and humanities.

In pursuing its mission, the EBF made many contributions over its 30-year history. The EBF helped to compile and make publicly available a digitized archive of audio recordings of Becker expressing his ideas and insights during debates and interviews, in 1972 and 1973, shortly before his death in 1974. The EBF helped make available a set of resources about Becker’s life, books, related work, and teaching tools. The EBF helped to cultivate a wealth of Becker-related pop-culture videos, interviews, and book and film reviews. And the EBF even helped create important materials to boost public engagement with Becker’s ideas, such as the award-winning documentary film Flight From Death (2003), the publication of the book The Ernest Becker Reader (2004), a community blog forum called The Denial File (2009-2023), and a professionally produced e-Zine titled This Mortal Life (2016-2023).

Becker’s and the EBF’s impact on the science of existential psychology

In the late 1970s and early 80s, Sheldon Solomon, Tom Pyszczynski, and Jeff Greenberg were grad students together in the experimental social psychology doctoral program at the University of Kansas. They were each interested in better understanding the fundamental motivations of human behavior—from the motivation to protect and enhance one’s self-esteem to the motivation to engage in intergroup or intercultural conflict. But, despite being able to observe these motivated behaviors in lab studies, they didn’t quite have a satisfying explanation of where those motivations were coming from. Then, in the early 1980s, Sheldon stumbled upon Becker’s books, shared them with Tom and Jeff, and suddenly they had a set of ideas that could explain why people strive for self-esteem and have such a difficult time getting along with people from other cultures.

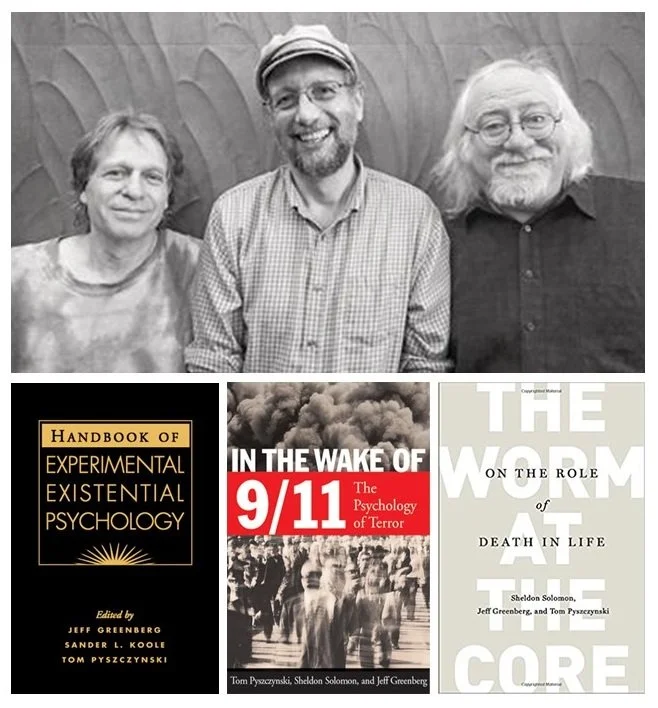

Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski developed terror management theory (TMT) from Becker’s ideas. Their milestone books: Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology (2004), In the Wake of 9/11; The Psychology of Terror (2003); and The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (2015).

The trio began to translate Becker’s ideas into terms familiar to their fellow social psychologists, distill them down into a set of testable hypotheses, and at the 1984 meeting of the Society of Experimental Social Psychology (SESP) they introduced these testable formulations as terror management theory (TMT). Although some of their colleagues were initially rather skeptical of these ideas, as the trio began conducting experiments a growing body of evidence emerged. Not only did their experiments provide compelling support for Becker’s ideas, but the process of developing and conducting research on TMT demonstrated to the field that it was indeed possible to apply the methodologies of modern psychological science to learn about existential psychological processes. Thus, the science of existential psychology was born.

Since then, the field has been busily applying the latest methods of psychological science to systematically study whether and how such core issues of “being” and “becoming” impact social and mental functioning, including: concerns about life and death, and the awareness of mortality; the challenges of authentic vs. inauthentic choices/actions; experiential isolation and a sense of shared reality; culture, self, and identity; meaning and purpose in life; religion and spirituality; and occasions for personal growth. Researchers in the field use a variety of tools, including correlational methods (is one variable systematically associated with another?), longitudinal methods (any changes across the lifespan?), or even experimental designs where researchers intentionally manipulate a variable to observe its causal impact on various psychological processes and social functioning.

Roughly twenty years after that initial 1984 SESP conference, researchers held an International Conference on Experimental Existential Psychology (2001), in Amsterdam, which led to a Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology (Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Koole, 2004) and landmark paper describing the new field in the journal Current Directions in Psychology Science (Koole, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 2006). In the roughly 20 years since, the field has continued to grow. We founded the International Society for the Science of Existential Psychology (ISSEP; issep.org) in 2019, with the overarching mission to encourage and support the scientific discovery, communication, and application of key research findings in existential psychology, and ISSEP has been providing a variety of supports, including: conference events for professionals in the field; pedagogical resources to advance teaching/learning; grant funding to support research studies; annual award programs to recognize notable contributions to the field; and digital Features & Spotlights that illustrate how existential psychological theory and research can help us better understand important human experiences, events, art, and culture.

ISSEP regularly celebrates the importance of Becker’s ideas to the development of the field. ISSEP awarded its inaugural Distinguished Career Contributions Award (2022) to Sheldon Solomon, Tom Pyszczynski, and Jeff Greenberg, in recognition of their pioneering research on Becker’s ideas, as described above. Additionally, ISSEPs Research Grants have funded Becker-related projects such as Rachel Menzies’ research on death anxiety and mental health (Menzies, 2022). ISSEP conference awards have funded Becker-related research presented at our annual Existential Psychology conferences, such as Stylianos Syropoulos’ research on death denial and legacy motivations, Dylan Horner’s research on death awareness and self-determination, or Ron Chau’s research on death and values. And ISSEP has sponsored original articles highlighting excellent Becker-related scholarship more broadly, such as Jamie Goldenberg’s work on the relationship between death denial and health (Goldenberg, 2022), Tom Pyszczynski’s work on the evolutionary development of death denial as an existential motivation (Pyszczynski, 2021), and Andy Scott and Jeff Schimel’s work on death denial and heroism (Scott & Schimel, 2021).

As a reflection of the EBF’s and ISSEP’s overlapping histories and interests, the EBF began sponsoring portions of ISSEPs annual Existential Psychology conference. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the EBF sponsored travel awards to support the attendance of ten student researchers at ISSEPs 2019 conference in Portland, OR and, ten more at ISSEPs 2020 conference in New Orleans, LA. During the pandemic, the EBF sponsored the professional networking events at ISSEPs virtual conferences in 2021 at Austin, TX, in 2022 at San Francisco, CA, and in 2023 in Atlanta, GA. The student scholars supported by the EBFs efforts came from diverse backgrounds and underrepresented groups, and presented research investigating Ernest Becker’s ideas about death denial as they pertained to legacy motives, heroism, politics and values, religious belief, and physical and mental health, just to name a few. As a testament to the EBF’s impact on this exciting new field, many of the young scholars supported by these EBF sponsored activities have secured academic positions at some of the nation’s best universities where they are continuing their important teaching and research.

ISSEP honors the legacy of Ernest Becker and the EBF

Counterclockwise from top left: A young Ernest Becker; Becker out doing some photography in Paris; students collecting signatures for the petition to keep Becker on at University of California, Berkeley; Becker writing at his desk.

Following the passing of the EBFs beloved founder and President, Dr. Neil J. Elgee, in 2020 at the age of 94, the EBF began considering ways to ensure Ernest Becker’s legacy would continue to be advocated for decades to come. Thus, the EBF began considering a major, long-term donation to ISSEP. Indeed, the EBF and the ISSEP share much in common—with overlapping historical and philosophical roots in Becker’s ideas, many years of shared goals and joint activities together, and a shared vision for the future of scholarly engagement with Becker’s ideas through the science of existential psychology.

In 2023, the EBF announced that after 30 successful years it would be closing its doors, devoting its support to ISSEP, and thus passing the baton for a new generation of Becker-related scholarship. As a result, the EBFs major donation will enable ISSEP to continue to honor the legacy of Ernest Becker, in a variety of ways, for decades to come.

First, ISSEP will continue to operate the EBF website—ernestbecker.org—as a resource for both the scholarly community and the general public. There, we will continue to celebrate the history and mission of the EBF; the site will continue to provide detailed information about Ernest Becker’s life, his intellectual contributions, and his books and related works; it will continue to make available the archival audio of Becker himself expressing his ideas in radio debates and interviews; it will continue to offer a wealth of resources such as videos, recorded webinars, and teaching tools; and it will make available the full collection of the interviews, the book and film reviews, entries in The Denial File (2009-2023), and all issues and articles published in This Mortal Life (2016-2023).

Second, ISSEP will launch an annual set of Ernest Becker Honors—including a research grant, an annual award, and conference awards. Each are designed to further explore the contributions of Ernest Becker and to further stimulate and recognize research contributions that expressly build on his work and ideas.

The Ernest Becker Research Grant is a grant program intended to both further explore the contributions of Ernest Becker and further stimulate research contributions in the science of existential psychology. This grant supports well-designed and well-powered studies that expressly build on the work and ideas of Ernest Becker and that have the potential to contribute to the scientific literature. Projects may use quantitative and/or qualitative methods, may rely on primary (e.g., original studies) or secondary data (e.g., meta-analyses), and may be basic or applied science.

The Ernest Becker Best Paper Award is an award program which will recognize excellence in papers that expressly build on the work and ideas of Ernest Becker in advancing the research, communication, and/or application of the science of existential psychology, including quantitative and/or qualitative research, theoretical advances, or systematic reviews of the scientific literature.

The Ernest Becker Conference Award supports the attendance and inclusion of emerging scholars presenting work, at ISSEPs annual Existential Psychology conference, which expressly build on the work and ideas of Ernest Becker in advancing the research, communication, and/or application of the science of existential psychology, including quantitative and/or qualitative research, theoretical advances, or systematic reviews of the scientific literature.

Third, ISSEP will cultivate and produce original Becker-related content on our own website—issep.org—each year. Contributions will include multi-media Feature and Spotlight articles about the Ernest Becker Research Grant projects, the advances recognized by the Ernest Becker Best Paper and Conference Awards, and other Becker-related material. The new articles that we will cultivate and produce each year will serve as yet another vehicle to further highlight and communicate knowledge related to Beckers work to the general public.