The 2018 film American Animals is a true-life heist thriller, and a brilliant docudrama. If you haven’t seen it, I recommend watching it before reading this, but that’s your call.

When American Animals showed at our terrific art cinema in Tucson, The Loft, I was intrigued by the title because my grad student Uri Lifshin and I conducted research on whether viewing oneself as an American helps many Americans avoid thinking of themselves as animals (it does). What could that title refer to then? As it turns out, a number of things.

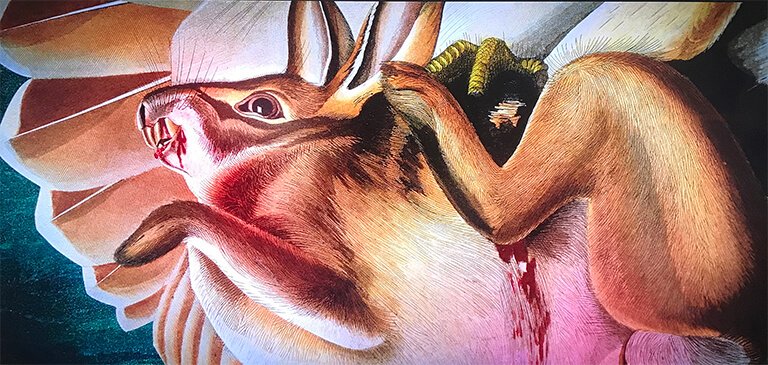

American Animals includes only one direct reference to death, which I will get to, yet it’s ripe for a Beckerian analysis. The movie opens with flashes of illustrations of predatory birds. It turns out the primary targets of the 2004 heist were two rare books from the Transylvania University library: Audubon’s The Birds of America—and a book by Charles Darwin. The birds portrayed in the former book are literally American animals, and the latter book by Darwin on evolution teaches us that the human beings who attempt the heist are American animals as well.

The film begins by telling us “This is not based on a true story, this is a true story.” It recounts an attempt by four relatively privileged college kids in Kentucky—kids set up for conventional success by their families and schooling—to steal those very valuable books. Actors portray the events as they unfold, but excerpts from interviews with the actual perpetrators are sprinkled throughout. Even though the viewer knows the caper will not work out, the portrayal of the actual heist is intense and harrowing because it shows how in the actual moment, the panic of animals under stress comes out, intensified by the exposure of the animality of the librarian they must subdue.

“You’re taught your entire life that what you do matters and that you’re special…when, in all reality, those things don’t matter. And you’re not special. And so the idea that we were doing this extraordinary thing absolutely appealed to us.”

Why would an aspiring artist, a scholarship athlete, a brilliant accounting student hoping to join the FBI, and an already accomplished entrepreneur decide to attempt such a heist? Because they had no sense that their lives were special and significant. And as Becker made clear, this is what we all want—to believe we are accomplishing something of enduring value that will be remembered and have an impact beyond our own lives, something that will last beyond death. For these young men, plodding along the culturally prescribed paths wasn’t promising them that. The film portrays moments of humiliation that the two real-life masterminds of the heist, Spencer and Warren, experienced that may have contributed to this disillusionment. As the young Warren says to the more reluctant Spencer, “What fucking future are you worried about? The one that’s fucking indistinguishable from everyone else’s, where you beaver away to get the shit you’re told you need to have by some fucking asshole who is going to tell you what a success you are once you have it all?” Reflecting back, the older Warren put it this way: You’re taught your entire life that what you do matters and that you’re special. And that, there are things you can point towards that would…which’ll show that you’re special, that show you’re different, when, in all reality, those things don’t matter. And you’re not special. And so the idea that we were doing this extraordinary thing absolutely appealed to us, appealed to me.”

There were numerous moments when Spencer wanted to abort the plan. At one point, Warren tells him, as way to dissuade Spencer from backing out that “one day you’ll be dead.” Ding ding ding! As Becker emphasized, this is why we are so motivated to strive to do something unique and special in our lives. In a subsequent scene, Spencer sees a flamingo cross a road, and this reminds him both of the Audubon book and of the value of experiencing something special.

And as Becker made clear, this is what we all want—to believe we are accomplishing something of enduring value that will be remembered and have an impact beyond our own lives, something that will last beyond death.

The more remorseful, older Spencer noted that “The pain I caused…was never worth the adventure we felt at the time or the change we were craving.” Of course, hindsight is 20/20, but at the time, despite plenty of doubts due to the risks of humiliating failure and prison, the four of them decided that it was worth the risks to do something special. They chose to be predators, to be cruel to serve their needs to be extraordinary. And, ironically, their botched heist did give them some basis for enduring significance by leading to the creation of a film that portrays them and their actions.

Is it wrong to tell our kids they are special, they are going to do great things? Is that the problem? Or is it a failure of the American worldview to help people feel that the social roles they aspire to and fulfill are of value?

From Becker’s perspective, the urge to heroism is inevitable, so it’s more the latter. The movie points to one of the problems—the individualistic nature of American culture. It’s not about being part of something valuable or great, you have to be special yourself. It’s too much for most of us to bear. So we either cross the line like these young dudes did or we recede into our shells, follow conventional cultural roles, and, if they are insufficient to afford us feelings of enduring significance, self-medicate away our residual anxieties with shopping, booze, and one’s drug of choice.

The other aspect of this is that, as noted by Becker in Escape from Evil, and my colleagues and me in The Worm at the Core, in any large, modern culture, it will be hard for most of its members to feel special because there will always seem to be many others doing the same thing we are doing, and some doing it better. Like the film, I’ll leave you to ponder this problem and its consequences further, and what could be done about it.

Jeff Greenberg is Professor of Psychology at the University of Arizona. He co-developed terror management theory, based on Becker’s writings, and the methods to investigate how awareness of mortality influences human behavior. He is co-author of Death in Classic and Contemporary Film (2013) and The Worm at the Core (2015).