RELIGION AS UMBRELLA, RELIGION AS PATH

A Buddhist Perspective on Becker

By David R. Loy

In his great book, The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker suggests that religions claiming knowledge of an afterlife create a “vital lie” and attempts to evade death and thus end up crippling us in life. But is religion nothing more than part of humanity’s collective childhood to be outgrown, like an infant’s security blanket, as we mature? Or is it possible that religion might help us mature? In other words, do religions also provide a path of self-transformation? Perhaps they are not only umbrellas to ward off the overpowering light of a truth we cannot cope with, or ideological drugs to control the masses. Can their teachings help us experience the world (and ourselves) differently, and live in the world more consciously?

For Buddhism, the issue is whether “salvation” is achieved by clinging to doctrines – that offer the possibility of a postmortem paradise, or by following a spiritual roadmap that can transform us here and now. What is perhaps most distinctive about Buddhism is the relationship it sees between our dukkha (suffering in the broadest sense) and our delusive sense of self that feels separate from the rest of the world. That the self is a psycho-social construction (in modern terms) implies a revision of Becker’s basic thesis about death-denial: for Buddhism, our basic repression is not awareness of mortality but what might be called awareness of one’s emptiness, or lack of self-existence. If the sense of self is a construct it is by definition ungrounded, hence intrinsically insecure, which we usually experience as a sense of lack that haunts the self. In response, we often feel a compulsion to make ourselves more real, in one way or another. In the contemporary U.S. that usually involves pursuing the symbolic reality supposedly conferred by lots of money, fame, power, or sexual attractiveness.

If the sense of a self inside is a construct, so is the external world, for when there is no inside there is no outside; the basic problem, then, is the sense of separation. The Buddhist solution to this predicament is rather simple although not usually easy to real-ize: the fictive, inherently anxious and insecure sense of self must let go, an “ego-death” that meditation promotes.

For Buddhism, the issue is whether “salvation” is to be achieved by clinging to doctrines and rituals that offer the possibility of a postmortem paradise, or by following a spiritual roadmap that can transform us here and now.

Here a door opens to something that remains to be explored by those who want to develop the religious implications of Becker’s work. The type of transcendence that Buddhism encourages does not necessarily involve escaping to some other (dimension of) reality, either now or after death, nor does it deny our creatureliness. Rather, it is a “turning around” (paravrtti in Sanskrit) that occurs at the core of one’s awareness, when I awaken to the fact that my true nature is nondual with the whole universe. The Japanese Zen master Dogen described his experience thus: “I came to realize clearly that mind is nothing other than mountains, rivers and the great wide earth, the sun, the moon and the stars.”

It would be easy for Becker to reject all such talk as another example of religious mystification, for that is the main direction of his argument. Yet, as his sympathetic treatment of Kierkegaard reveals, he himself is conflicted on this issue.

…the fictive, inherently anxious and insecure sense of self must let go, an “ego-death” that meditation promotes.

This perspective amounts to a challenge for Buddhism (and other religions) to grow up. If religious language is basically metaphorical and symbolic, as scholars of religion keep reminding us, religions today need to de-emphasize dogma about an afterlife in place of ego-self deconstruction and reconstruction, which can transform how we experience the world, including ourselves, right here and now.

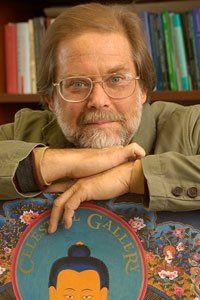

David Robert Loy is a professor, writer, and Zen teacher in the Sanbo Kyodan tradition of Japanese Zen Buddhism.

He is a prolific author, whose essays and books have been translated into many languages. His articles appear regularly in the pages of major journals such as Tikkun and Buddhist magazines including Tricycle, Turning Wheel, Shambhala Sun and Buddhadharma, as well as in a variety of scholarly journals. Many of his writings, as well as audio and video talks and interviews, are available on the web. He is on the editorial or advisory boards of the journals Cultural Dynamics, Worldviews, Contemporary Buddhism, Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, and World Fellowship of Buddhists Review. He is also on the advisory boards of Buddhist Global Relief, the Clear View Project, Zen Peacemakers, and the Ernest Becker Foundation.

David lectures nationally and internationally on various topics, focusing primarily on the encounter between Buddhism and modernity: what each can learn from the other. He is especially concerned about social and ecological issues. A popular recent lecture is “Healing Ecology: A Buddhist Perspective on the Eco-crisis”, which argues that there is an important parallel between what Buddhism says about our personal predicament and our collective predicament today in relation to the rest of the biosphere. Presently he is offering workshops on “Transforming Self, Transforming Society” and on a recent book. He also leads meditation retreats. (To find out about forthcoming lectures, workshops and retreats, please see his website.)