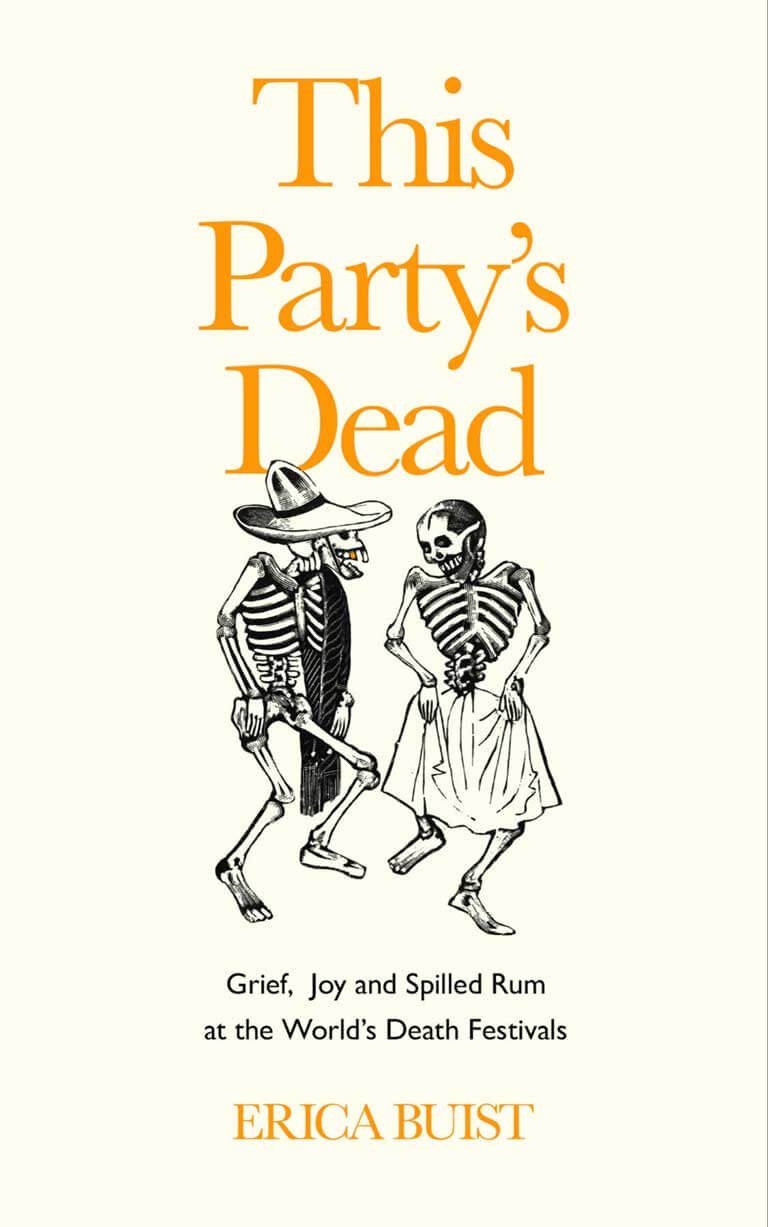

Erica Buist is a writer, journalist and lecturer living in London. She recently travelled to seven death festivals (in Mexico, Nepal, Sicily, Thailand, Madagascar, Japan, and Indonesia), to try to understand how people from different cultures deal with mortal terror, after being very unsatisfied with the Western way of doing things. She wrote a book about the journey called This Party’s Dead. Erica writes for the Guardian and has also contributed to publications such as the BBC, the Mirror, Medium, Newsweek, and various literary anthologies. She has lived in Mexico and Paris and speaks five languages – mainly to her dog.

She tweets @ericabuist.

Photos and video footage of the death festivals can be found on Instagram @thispartysdead

After your incredible journey to seven death festivals, how do you think your personal life has changed?

Before I started, I was terribly afraid of death, but in a really unexamined way. I come from a medical family, and my parents are very much the stereotypical, terrified-of-death kind of medics. I was raised to be afraid of death as well; death was this unmentionable, terrifying thing. The point of going to visit the death festivals was not to deal with my own terror – this was not Eat, Pray, Love with corpses. I would never say to someone that the way to deal with grief or death anxiety is to visit a bunch of countries. But I had become obsessed with this idea of death anxiety after my father-in-law passed and I became agoraphobic. I remember thinking at one point, “How is it that in Mexico they see death and throw a party?” That seemed so stark to me. Now that I’ve visited them, I would say that it’s almost impossible for anything to keep its power to frighten you when you look at it over and over and over. It’s as if you thought there was a monster in the dark and you turn on a light and it turns out to be a cat. It’s still not something you want smothering your face, but it’s not what you thought. I guess that’s where my personal life has changed. Death is somewhat demystified for me. It’s no longer this thing that I’m trying not to look at; I’ve now looked at it square in the eyes and thought “Okay, I know what you are now.”

You say “perhaps balance is the key to a better relationship with death; something between the horror of finding the decomposing corpse of a loved one and a sanitized, soulless goodbye.” How have you found that balance?

In most of the places I’ve gone, death lives just a little bit closer. Like Mexico for example. In the last decade, only Syria has had a higher rate of unnatural death than Mexico. In the West we’re so used to having death come naturally, or at least somewhat self-inflicted by our lifestyles, and usually later in life. When I picture my own death, I picture myself old, in a hospital, with doctors yelling “Stat!” And what does that say? It says that I’m incredibly privileged: to expect that I’ll reach old age, that I’ll be in a system that’s going to take care of me. And why am I picturing people yelling stat? Because where I live it’s natural to assume that people are going to pull out all the stops to save me, because preventing my death is seen as really important. I’m acknowledging that privilege a lot more now, but it also shows that here death is seen as an aberration, something to be avoided at all costs, rather than something that’s normal.

Through all the festivals that you visited did you ever think to yourself that it was all just varying degrees of elaborate denial?

Yes and no. On the yes side, of course, partly because I’m an atheist. I didn’t decide to be one, but when someone asks what you believe, you reach into your chest and pull out what’s there, and for me it’s, “Oh yeah, we’re alone, and this is all chaos.” So for a lot of it, I did think this is people sort of dancing around their terror of death, trying to pretend that we’ll all somehow survive it. Like on the Day of the Dead, they believe the dead are coming back to visit (this is also the basis of the death festival I visited in Japan). In Madagascar they actually dig up the corpses and have a party with them; when you die there, they believe that your power increases, rather than disappears. The ancestors are the ones you pray to for health and a decent harvest. So you could naturally see that as a straight-up denial that death takes anything from you.

But it was a good couple of years into the project before I worked out the actual point of the death festivals. I’m not saying that there is no denial, but when someone dies, your love doesn’t go anywhere. I’m sure you’ve heard people say, “grief is just love with nowhere to go,” but why do we just accept that there’s nowhere for it to go? We’re so secular and unenchanted that we just go, “ah well, what can you do?” Well, you can do something. And that’s what the death festivals are, I think, really for.

I think the reason that these people do deal with death a little bit better than we do here in the West at varying degrees, is that when you have a death festival, you are forcing the brain to focus not just on your grief for the people you lost, but on mortality itself. You’re pouring them a drink. You’re setting up offerings, you’re thinking about them. You’re taking care of them. You’re wrapping them in a new shroud and with all these acts of care, giving your love somewhere to go. So yes, it’s denial, but it’s also the opposite of denial. It’s facing something we don’t face here.

it’s almost impossible for anything to keep its power to frighten you when you look at it over and over and over.

Becker talks about the best illusion being one that harms the fewest people. Do you have any thoughts on what the healthiest version would look like, in an ideal world? Or what you would take if you could take the best parts of the festivals and rituals you’ve seen?

I’d like to mix two things. I would mix the belief that they have in Madagascar, which is that you increase your power when you die. I think it makes death a lot less anxiety-provoking. Here, we think of death as the loss of all our power, I think because in a capitalist society you’re valued on your output, and obviously when you’re dead your projects are over. The harshest way I’ve heard it put is that when you die, you don’t matter anymore. And the consequence of that is that you lose value in society as you get older; the closer you get to death, the less you matter. And that must be terrifying. And I know it’s terrifying, particularly because as women, we start to lose our value ridiculously young, because we’re valued on our beauty and our baby-making, and the latter is also used to keep us out of the workforce. So it’s already a struggle as a woman to be worth something by the metrics society’s laid out. So it’s this “cult of busy” that is weaponized all the time, but we’re really shooting ourselves in the foot creating this culture of “you are what you do”, because we’re all going to get old and do less, so we’ve doomed ourselves to a fate of mattering less and less. So that thing of your power increasing in death is huge because it makes you less afraid of mortality and also means that you’re valued more the closer you get to it, not less. And the people left behind are thinking about the dead and they are not saying “poor her, she’s dead.” They’re saying, “oh, I miss her, and now I’ll ask her for high exam grades and good health.” I think that is a type of illusion, to use Becker’s word, that’s really healthy.

The second thing I would like to take is the concept of an annual visit because I think this is healthy for the people left behind. It’s time and mental space that you carve out to think about the dead and to consider your mortality. And that little bit of space makes so much difference. In the end of the Mexico chapter, I force myself to go and talk to my deceased father-in-law. An English atheist talking to a photograph, can you imagine how awkward? But straight away I went and put something in my calendar, and I hadn’t used my calendar for a year because after he died it chirped the reminder “Birthday dinner with Chris!” and I’d just stopped using it. My life had been a series of haphazard lists, and suddenly, without thinking, I just put something in my calendar, like it was nothing, then realized what I’d done. If I were a spiritual person, I would probably interpret that as him sending me a message, helping to heal me. But I think I just gave myself basic self-care, time and space and engaging with the thing that had been hurting me, and suddenly a tiny bit of acceptance just clicked. And I stopped running away from calendars.

Ma’nene Festival in Tana Toraja, Indonesia