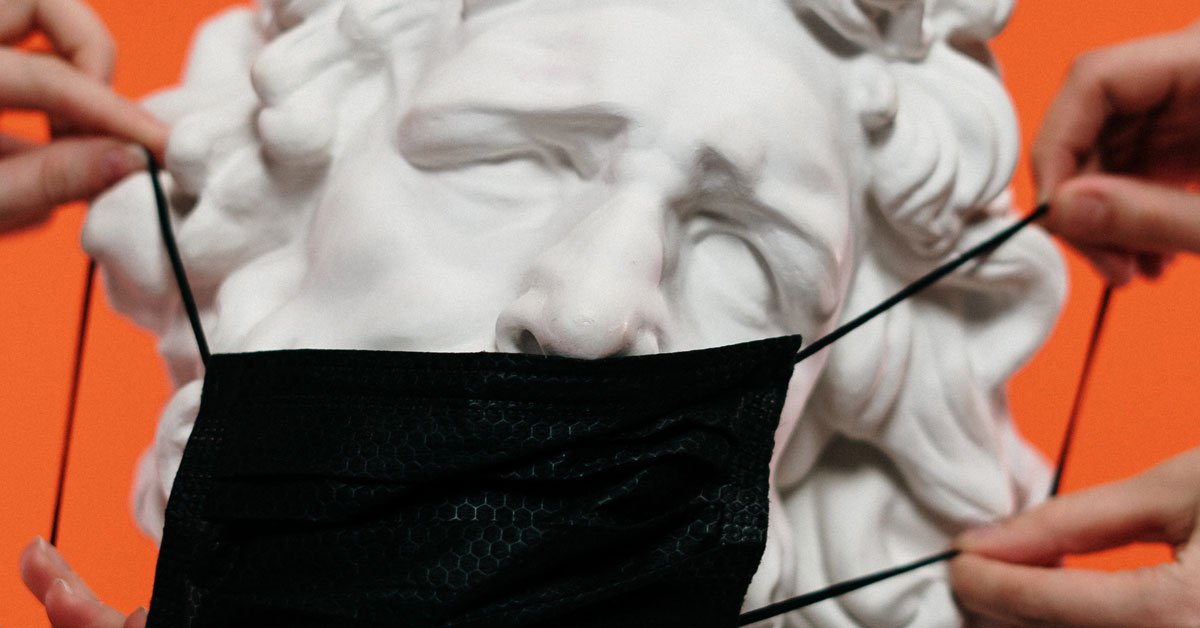

Do Not Muzzle My Masculinity: Men and Face Masks During COVID-19

By Nikita Rattu | March 11, 2021

Globally, there have been over 100 million reported cases and over 2 million deaths attributed to COVID-19,1 classifying the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic.2 One way that people might minimize their risk of infection, as well as virus transmission, is by wearing a facemask.3 Indeed, many places across the globe have attempted to make facemask-wearing mandatory in public. However, studies suggest that males have lower intentions to wear facemasks than females.4 For example, a study of retail shoppers in the United States in the summer of 2020 found that females were 1.5 times more likely to wear a facemask, compared to males.5

Due to COVID-19’s association with death, reactions to the pandemic might be driven by some uniquely human existential concerns.6 Terror Management Theory (TMT), inspired by Ernest Becker’s work, suggests that people manage death thoughts by maintaining cultural worldviews and adhering to standards of conduct developed according to these worldviews.7 Thus, through an analysis of a “masculine” worldview, Becker’s work may provide valuable insight into why some males might be less likely to wear a facemask during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Becker and TMT, males may wear facemasks less as a way to maintain and reinforce their “masculine” cultural worldview. Humans need to live up to socially validated standards, in order to feel that life has purpose and we are valued individuals.8 Masculinity, at least as is commonly established in Western culture, can be described as being strong, fearless, and not showing vulnerability.9 For example, males who score higher on a masculinity ideology scale are shown to have a more negative outlook on seeking psychological help.10 This suggests that males are more reluctant to accept aid for health-related issues as this conflicts with their masculine worldview that portrays men as tough and self-sufficient.

More directly, an online study examining intentions to wear a facemask in the U.S. found that males perceived wearing face masks to be “shameful, not cool, a sign of weakness, and a stigma”.11 The perception that wearing a facemask makes an individual appear weak may suggest that wearing one threatens an individual’s sense of masculinity. Thus, not wearing a facemask could be considered a form of worldview defense, in an attempt for males to reassert their masculinity. In turn, this may provide males with a sense of self-esteem that manages the awareness of death. This attempt to bolster a sense of masculinity might be heightened particularly during the pandemic, as it is a critical reminder of life’s impermanence.

However, it is essential to note that this action has not been unanimously demonstrated by all males. Indeed, the majority of males do wear facemasks, and have only been observed to wear them less in comparison to women.4, 5 This might be because the detrimental influence of masculine worldviews is dependent on the extent to which an individual identifies with such conventional Western ideals of masculinity.

In addition to these distal, worldview-maintaining responses that aim to bolster self-esteem by reasserting masculinity, TMT argues that humans also manage reminders of death through proximal defenses.12 These defenses are activated directly in response to conscious reminders of death, with the goal of minimizing threat, suppressing death thoughts and managing threats to mortality, such as health threats.13 Males might also be more likely to exhibit health-defeating behaviors/proximal defenses in response to COVID-19, as males tend to underestimate risks to oneself, compared to females.14 Indeed, this effect appears to also be present in the pandemic, as an international study across Europe, America, and Asia found that males perceived COVID-19 as less dangerous than women.15 Thus, males may put themselves more at risk via both proximal and distal responses to the pandemic.

Overall, using TMT to explain this phenomenon allows us to more deeply understand the behavior and choices made by people in the unpredictable period of a pandemic. Indeed, as this analysis shows, existential concerns may promote health-defeating behaviors. This can potentially explain why an individual might actually put themselves at greater risk, by not wearing a face mask, in an effort to prove to themselves that they are not vulnerable. While this may increase one’s own chance of catching a potentially fatal disease, the choices made by these individuals also increase the risk to others. Ultimately, this emphasizes how vital the maintenance of cultural worldviews and self-esteem is, as humans appear to go to potentially deadly lengths to feel culturally validated.

Nikita Rattu is a psychology undergraduate who would like to pursue a career in Clinical or Marketing Psychology. She is interested in Anxiety Disorders, OCD and Depression, as well as what motivates consumer behavior. She was taught about the works of Terror Management Theory and Ernest Becker by Dr Samuel Fairlamb at Royal Holloway, University of London.

References

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering. (2021, January 05). Retrieved from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Boseley, S. (2020, March 11). WHO declares coronavirus pandemic. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/11/who-declares-coronavirus-pandemic

Chu, D. K., Akl, E. A., Duda, S., Solo, K., Yaacoub, S., & Schünemann, H. J. (2020). Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis, The Lancet, 395, 1973-1987.

Chuang, Y., & Liu, J. C. E. (2020). Who wears a mask? Gender differences in risk behaviors in the COVID-19 early days in Taiwan. Economics Bulletin, 40(4), 2619-2627.

Haischer, M. H., Beilfuss, R., Hart, M. R., Opielinski, L., Wrucke, D., Zirgaitis, G., Uhrich, T. D., & Hunter, S. K. (2020). Who is wearing a mask? Gender-, age-, and location-related differences during the COVID-19 pandemic, PLOS One, 15(10), e0240785.

Courtney, E. P., Goldenberg, J. L., & Boyd, P. (2020). The contagion of mortality: a terror management health model for pandemics, British Journal of Social Psychology, 59, 607-617.

Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., & Pyszczynski, T. (1997). Terror Management Theory of self-esteem and cultural worldviews: empirical assessment and conceptual refinements, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 61-139.

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (1991). A terror management theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of self-esteem and cultural worldviews. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 93-159.

Boon, K. A. (2005). Heroes, metanarratives, and the paradox of Masculinity in Contemporary Western Culture. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 13(3), 301-312.

Berger, J. M., Levant, R., McMillan, K. K., Kelleher, W., & Sellers, A. (2005). Impact of Gender Role Conflict, Traditional Masculinity Ideology, Alexithymia, and Age on Men’s Attitudes Toward Psychological Help Seeking. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(1), 73.

Capraro, V., & Barcelo, H. (2020). The effect of messaging and gender on intentions to wear a face covering to slow down COVID-19 transmission. arXiv, preprint arXiv:2005.05467.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1999). A dual-process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: an extension of Terror Management Theory. Psychological Review, 106(4), 835-845.

Arndt, J., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2017). Where health and death intersect: insights from a Terror Management Health Model, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(2), 126-131.

Finucane, M. L., Slovic, P., Mertz, C. K., Flynn, J., & Satterfield, T. A. (2000). Gender, race, and perceived risk: the ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society, 2(2), 159-172.

Dryhurst, S., Schneider, C. R., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L. J., Recchia, G., van der Bles, A. M., Spiegelhalter, D., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world, Journal of Risk Research, 1-13.

Additional References

Arndt, J., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1997). Subliminal exposure to death-related stimuli increases defense of the cultural worldview. Psychological Science, 8(5), 379-385

Butler, S., & Murphy, S. (2020, July 23). Face masks mandatory in shops, takeaways and stations in England from Friday. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/23/face-masks-mandatory-shops-takeaways-stations-england-friday

Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The Meaning Maintenance Model: on the coherence of social motivations, Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88-110.

Jin, J. M., Bai, P., He, W., Wu, F., Liu, X. F., Han, D. M., Liu, S., & Yang, J. K. (2020). Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality, Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 1-6.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review, Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435-468.